How Does Subscription Term Differ From Maximum Possible Term?

- Contributor

- Dean Michael Mead

Mar 29, 2023

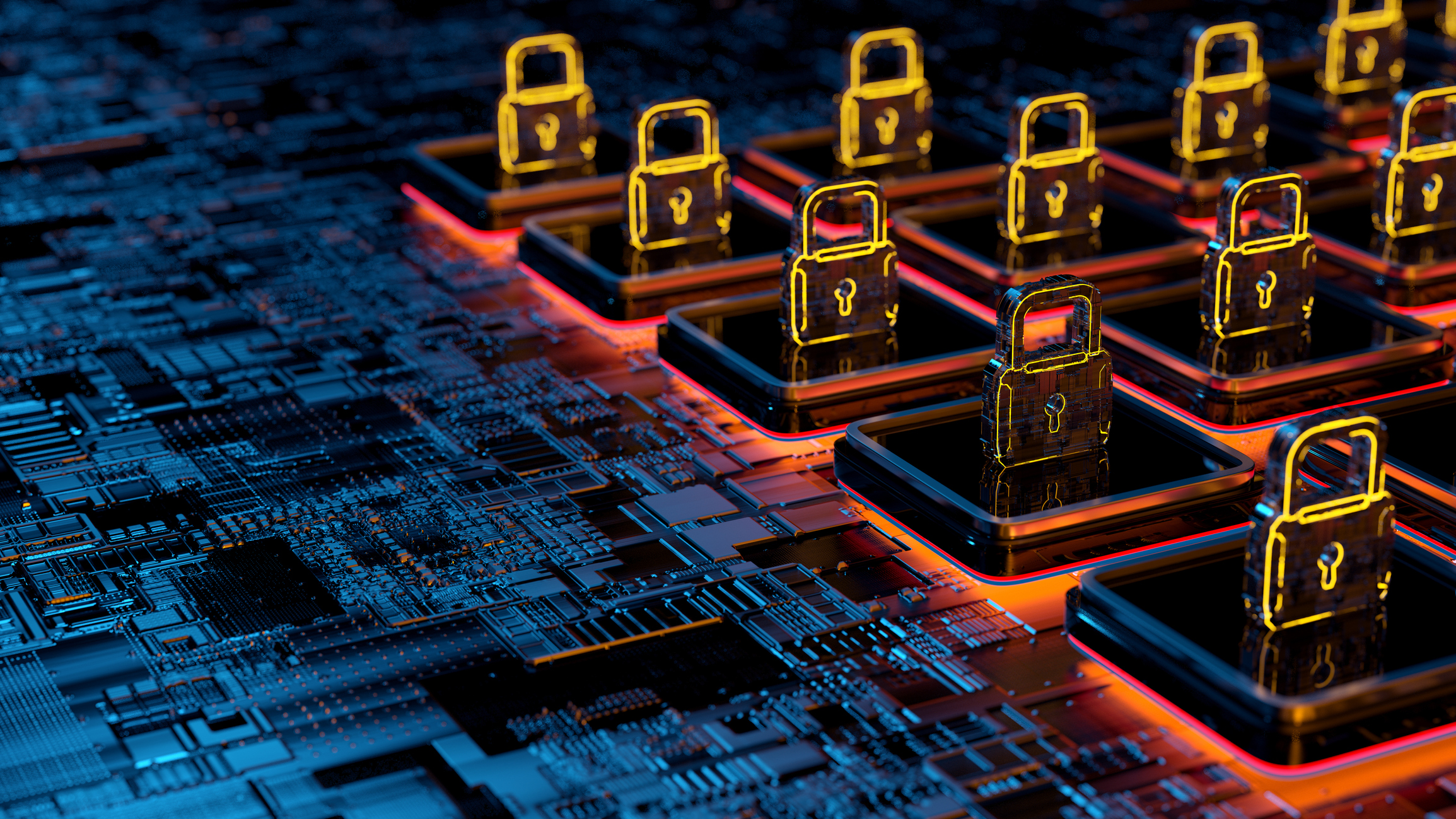

A recent article from CRI distinguished between two similar provisions of Governmental Accounting Standards Board (GASB) Statement No. 87, Leases, that are often confused: maximum possible term and lease term. Because the general approach to leases in Statement 87 is also used in GASB Statement No. 96, Subscription-Based Information Technology Arrangements (SBITAs, such as many cloud computing transactions), it’s important to understand how maximum possible term and subscription term differ as well. (For a brief overview of Statement 96, check out this article from CRI.)

Maximum Possible Term: Is a SBITA a “Short-term SBITA”?

Just as you did for leases when implementing Statement 87, one of the first questions you must ask when applying Statement 96 is whether SBITA is a short-term SBITA. That is because the general model for recording the financial side of a SBITA and measuring the amounts reported in financial statements applies only to SBITAs that are not short-term. Rather than booking an intangible right-to-use subscription asset and a subscription liability, the only accounting for short-term SBITAs is reporting the subscription payments as expenses. The short-term SBITA accounting is less burdensome than the general model.

A short-term SBITA is defined as one that “at the commencement of the subscription term, has a maximum possible term under the SBITA contract of 12 months (or less), including any options to extend, regardless of their probability of being exercised.” Determining a SBITA’s maximum possible term is solely related to this purpose—it has no other function in the standards.

Subscription Term: How Long Does a SBITA Run?

For SBITAs that are not short-term, a government measures its subscription liability in part by discounting future payments over the course of the arrangement to their present value. An essential step in that process is determining the subscription term—the period over which those payments will be made.

Why Are the Two Concepts Confused?

Apart from having similar names, many of the building blocks of the maximum possible term and subscription term are the same:

| Periods | Maximum Possible Term | Subscription Term |

| Noncancelable | Included | Included |

| Either the government or the vendor has the option to extend | Included regardless of the likelihood the option will be exercised | Included if the option is reasonably certain to be exercised |

| Either the government or the vendor has the option to terminate | Not applicable | Included if the option is reasonably certain not to be exercised |

| Both the government and the vendor have the option to terminate | Excluded | Excluded |

| Both the government and the vendor must agree to extend | Excluded | Excluded |

Both the maximum possible term and the subscription term include periods (years, months, days) during which neither the government nor the vendor can end the SBITA—called noncancelable periods. Both exclude periods containing “two-way” options—when both parties can end the SBITA without the other’s permission or when both parties must agree to extend the SBITA.

Maximum possible term and subscription term differ regarding the circumstances under which they include periods with “one-way” options—either the government or the vendor has the option to extend or terminate. The subscription term includes periods with one-way options to extend if it is reasonably certain that the party will exercise the option. It also includes periods with one-way options to terminate if it is reasonably certain that the party will not exercise the option.

On the other hand, the maximum possible term includes all periods with one-way options “regardless of their probability of being exercised.” The primary source of confusion with this aspect of Statement 96 (and Statement 97 before it) is the mistaken view that the evaluation of “reasonably certain” is relevant to determining the maximum possible term; it is not.

Examples

A few simple examples illustrate the difference between the maximum possible term and the subscription term.

Example 1: A government enters into a contract with a 6-month noncancelable period and an option to extend a further 12 months. It is reasonably certain that the government will exercise the option to extend.

This is not a short-term SBITA because the maximum possible term is 18 months—the 6-month noncancelable period plus the 12-month extension. The subscription term also is 18 months—the 6-month noncancelable period plus the 12-month extension because it is reasonably certain to be exercised.

Example 2: A government enters into a contract with a 6-month noncancelable period and an option to extend a further 12 months. It is not reasonably certain that the government will exercise the option to extend.

This is not a short-term SBITA because the maximum possible term is 18 months—the 6-month noncancelable period plus the 12-month extension. The subscription term, however, is just the 6-month noncancelable period; the 12-month extension is excluded because it is not reasonably certain to be exercised.

Example 3: A government enters into a contract with a 6-month noncancelable period; both the government and the other party have the option to extend a further 12 months.

This is a short-term SBITA because the maximum possible term is just the 6-month noncancelable period; because both parties have the option to extend, the additional 12 months are excluded. Therefore, the subscription term is not evaluated because it is relevant only to SBITAs that are not short-term.

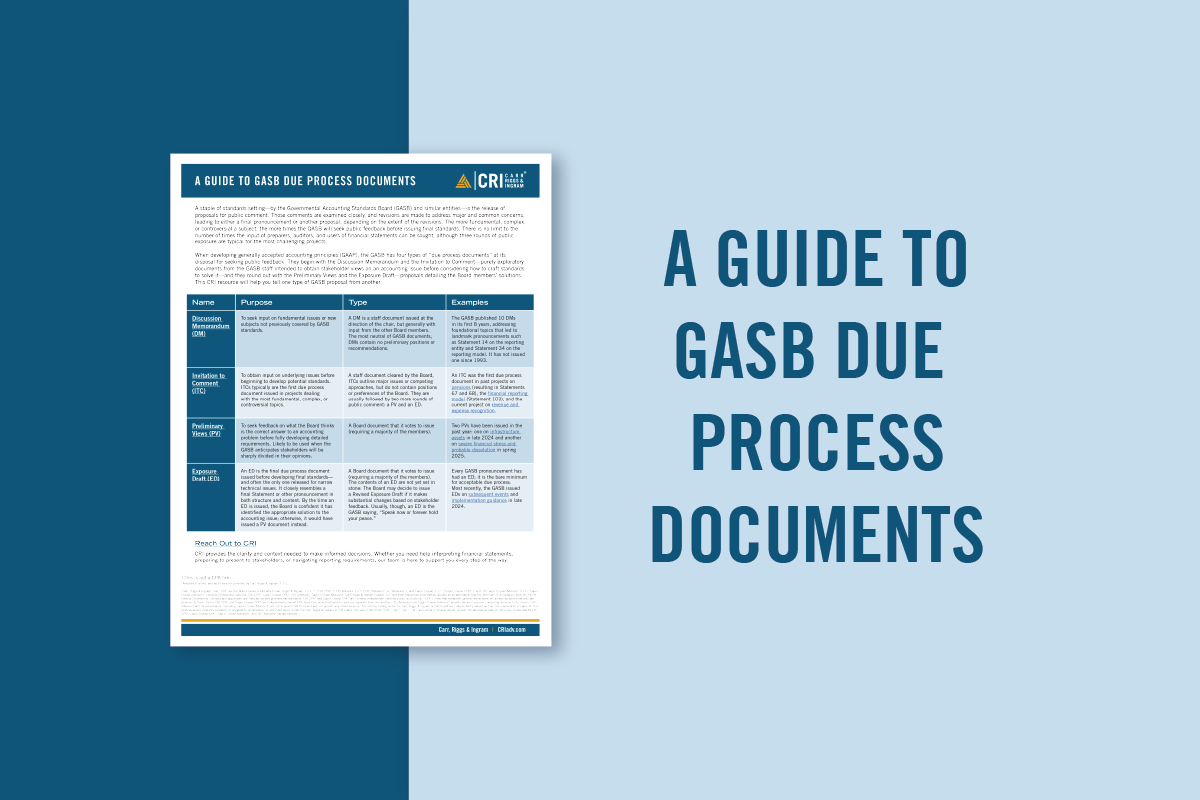

Assistance With the SBITA Standards

If you need help implementing the SBITA standards, don’t hesitate to contact CRI. Our user-friendly software, CentraLease, simplifies implementation and ongoing compliance and can be employed for both leases and SBITAs.